7 September 2023: added a note to the section Establishedness and

the Cross.

22 May 2023: changed link from Twitter conversation to archives

of Twitter conversation in preparation for me deleting my Twitter

account.

Epistemic status: contains innovations on past ideas

of mine which I may not have thoroughly thought through before posting

this, so there's an element of provisionalness to this. (And new, even

more provisional ideas.) Also, tries to say something about parts of

the Bible, when ideally I should have read the whole Bible with an eye

to the themes in here.

I suspect that there are details which are poorly explained or

contradictory somewhere in this. If you are confused about something,

let me know in the comments so I can address the problem.

This is the long version of this post. It's about as long as a book.

The short version is here.

I am not entirely proud of this (as a writer), but perhaps that is

fitting, as you will see. Realistically, I think it's the best version

of this that I can produce at this time.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1

Part 1: Initial Thoughts

1.1

Introduction

1.2

Why Firm, Consistent Governments Can Be Good

1.2.1

They can have good consequences

1.2.2

Governments may look like gangs, but they don't have to

1.3

A Person Might Not Want to be Told What to Do

1.3.1

Maybe all of this pales in comparison with whether we love God

1.4

Summary / Keeping Score

1.5

Kingship and Individual Liberty May Not Have to Conflict

1.6

King as Legislator Yields Libertarian Kingdom

1.6.1

My Church of Christ background probably connects to my views

1.7

What is the Real Issue?

1.7.1

Is it "How should government look on earth?"

1.7.2

Is it "How should we relate to the ideas of kingship and law?"

1.7.3

Which is better for developing trust, hands-off, or hands-on government?

1.7.4

The danger of wealth

1.7.5

The value of poverty

1.8

Closing Section

1.8.1

More considerations of wealth and establishedness

1.8.2

Conclusion of Part 1

2

Part 2: Judges, Saul, David, Solomon

2.1

My New Wine Background

2.2

Synopsis

2.3

Episodes

2.3.1

Note on translations

2.3.2

Gideon (Judges 6 - 8)

2.3.3

God Says He Will Abandon Israel and Then Doesn't (Judges 10)

2.3.4

The Judges System Isn't Working (Judges 17 - 21)

2.3.5

The People Choose to Have a Human King (1 Samuel 8)

2.3.6

God's "Regret" (1 Samuel 15)

2.3.7

Uzzah Tries to Save the Ark (2 Samuel 6)

2.3.8

David's Census (2 Samuel 24)

2.3.9

Solomon's Impressiveness (Temple, Wealth, Wisdom) (1 Kings 5 - 10)

2.3.10

Solomon Falls Away (1 Kings 11)

2.4

Overall

3

Part 3: Subsequent Thoughts

3.1

Introduction

3.2

Notes

3.2.1

Philosophy

3.2.1.1

The truth and orthodoxy

3.2.1.2

Establishedness is trust-producing

3.2.1.3

Ambiguity and mixedness, definitions

3.2.1.4

How to be a Christian given mixedness

3.2.1.5

"Unlackingness": Perfection or Reality

3.2.1.6

Mixedness does not prevent altruism

3.2.1.7

Some things ought to be permanently

3.2.1.8

The mixedness of bringing to justice

3.2.1.9

God's trustworthiness despite his disestablishedness or less-established approach to relating to us

3.2.1.10

Trust vs. physical survival

3.2.1.11

Disestablishedness is established

3.2.1.12

Being is personal and therefore partially disestablished

3.2.1.13

Trust

3.2.2

Psychological, Social, Spiritual

3.2.2.1

Belonging to a group may inhibit intimacy with God

3.2.2.2

If we don't value poverty sufficiently, we lose the ability to benefit from it

3.2.2.3

Seeing by fighting

3.2.2.4

Mixedness of upbringing

3.2.2.5

Relying on others to shield ourselves from reality

3.2.2.6

Fans seek establishedness

3.2.2.7

Danger of bad establishedness

3.2.2.8

Kinglessness, spouselessness

3.2.2.9

Good and bad establishedness

3.2.2.10

Rejecting establishedness as protest

3.2.2.11

Political fights

3.2.2.12

Kings obey laws

3.2.2.13

Becoming yourself is a natural but dangerous move

3.2.2.14

Valuing the firmness of true establishedness

3.2.2.15

Law and king prevent petty kingships

3.2.2.16

Disestablishedness in growing up

3.2.2.17

Relying on other than God

3.2.2.18

David, more fortunate

3.2.2.19

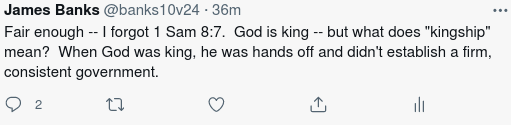

God is king means... ?

3.2.2.20

Going from disestablished to established is spiritually fortunate

3.2.3

Political

3.2.3.1

Political disestablishedness must be worked for

3.2.3.2

Is this Christian anarchism?

3.2.3.3

International establishments

3.2.3.4

Politics emphasizing relationship with God

3.2.3.5

Collective identity of Jews in Captivity as trustworthy for political establishedness

3.2.3.6

The Northern Triangle may be worse than Judges-era Israel

3.2.4

Personal

3.2.4.1

Personal scale kings

3.2.4.2

Fighting Evil

3.2.5

Mourning

3.2.6

Monasticism

3.2.6.1

Worry when temptations cease

3.2.6.2

Monasticism as institutionalized disestablishedness

3.2.6.3

Celibacy as establishedness in the desert

3.2.6.4

Asceticism could be a disestablishedness that causes you to love and trust God

3.2.6.5

Monastic disestablishedness of watchfulness

3.2.7

Current Events

3.2.7.1

A truly Christian nation would be less established

3.2.7.2

Not voting because I'm okay with disestablishedness

3.2.7.3

Climate change will disestablish but there's likely a time after that

3.2.7.4

That a disestablished world can be valuable makes anti-abortion sentiment sensible

3.2.7.5

Fraternity of disestablishedness

3.2.7.6

Recall Day

3.2.8

The Cross

3.2.8.1

Refounding with the cross

3.2.8.2

Establishedness and the cross

3.2.9

Church

3.2.9.1

Dangers of establishment Christianity

3.2.9.2

The spiritual danger of there being a scholarly consensus on the Bible

3.2.9.3

Can New Testament and Old Testament vibes coexist?

3.3.9.4

Progressive and Conservative Christians are both humanists, in a way; there's such a thing as theism

3.2.9.5

Church as a safe place for danger

3.2.9.6

The church could be like Solomon and be a bad establishedness

3.2.10

Conclusions

3.2.10.1

Eternal lack and fullness as good disestablishedness

3.3

Conclusion

4

Appendix: notes from Bible reading

I had a Twitter conversation with Susannah Black

(@suzania).

It got to the point where I felt like I wanted to reply with a

blog post instead of trying to work with Twitter's format, so I

wrote this.

(Apologies to my interlocutor (Susannah Black) for how long this

took me to write. This first part I finished in a day or two and

should be seen as more or less what I would have said in conversation

on the day of our Twitter exchange, while the following parts reflect

later thinking. I considered rewriting this first part to make it more

presentable, but decided not to, other than what was necessary for

clarity. Also, this post grew to be long -- at least it will not be

as long to read as it was to write.)

Here is the context: Black quote re-tweeted someone's take

about libertarians (governor of Florida is apparently being a libertarian

by being more or less laissez-faire about COVID). That take referenced

a Washington Post article which was paywalled for me, so I didn't read

it. I replied to Black mainly based on the object-level of her tweet,

but I can see that she may have read into me some sort of support for

the governor of Florida (or similar people or ideas), given that I was

in some sense pushing back against something that she said in response

to people like the governor of Florida. I don't support the governor

of Florida, nor have much of a sense of opposing him. (I have been

vaccinated, and I don't mind being masked or even being under lockdown

(mostly) so those preferences and actions may show that I trust the

values that oppose the governor. But I don't feel like I oppose him, or

even whatever it is that he represents, of which he is only the visible

instantiation of the day.)

Here are the tweets [or archived from Twitter:

1

2

3

4

5

(6 is the tweet from someone else in case you want

to account for all tweets replying to the original tweet)]:

And here are two branches of the thread:

(I could have made those images look better, but it may not be important,

as the reader may see below.)

I will try to reply to Black's question

Q: does "kingship" seem like a bad thing to you? Does "firm,

consistent government" have the flavor of "bossy tyranny" when you hear

it?

Also I will consider what value there might in less "firm, consistent"

government and in libertarian or liberal values. Then I will consider

what the nature of kingship could be or ought to be: king as direct leader

vs. king as legislator and facilitator? Hopefully this all will address

most of the issues raised in the tweets.

I don't think that "firm, consistent government" has the flavor of "bossy

tyranny" to me. I don't mind authority, personally. In many ways, the

relatively firm, consistent government of the United States makes many

things possible for me. In a sufficiently chaotic world, I might not be

alive today, to be able to write things. I've been reading [had read and

intend to re-read] A History of Violence by Óscar

Martínez to learn about the Northern Triangle (which comprises the

countries of Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras). Gangs like MS-13 are

very powerful there. There are something like 10,000 MS-13 members in the US,

which, if you read the book, you realize is more than enough to do a lot

of damage, but the ones who live here generally don't make the national

news, probably because our government is "firm and consistent" (has the

resources to enforce its laws fairly well). A failed state allows horrors.

I don't think libertarians want Northern Triangle-like situations, and

they don't think libertarianism would inevitably lead to them. Libertarians

can be minarchists (or something like that) who prefer a strong state when

it comes to enforcing protections of liberty. But they are perhaps not

the most libertarian of libertarians -- anarcho-capitalists are, perhaps.

[These are the libertarians who might be assumed to be most against "firm,

consistent" government.]

You could push back against an anarcho-capitalist and say

"why wouldn't anarcho-capitalism turn into the Northern Triangle?" MS-13,

Barrio 18, Los Zetas, and other gangs seem to be independent firms doing

what they want -- some even take over some government services. The

difference between a gang and a government is somewhat fuzzy. Do you

need one big, authoritative gang that is able to squash the other gangs,

so that there isn't so much gang warfare? That may be what liberals have

in mind. (Set up the messed-up thing that limits the even more messed-up

things.) And libertarians, with that dark view of the reality of

government as it actually gets established, want less of it. They seem

to think that darkness comes from government itself, since governments

can be dark.

Black is affiliated with the "post-liberals" / "Christian humanists".

From a bit of a distance, it looks to me like their approach is to say

"there is a good version of things and we can have it on earth". So there

is a really good government. And we can have a really good government

on earth (maybe). (A really good army? A really good police

force? We're not talking about a really ideal world, if there still needs

to be an army or a police force.) Certainly if you remember that there

can be a really humane world, and you believe that it is realizable, you

may be able to have it, which is less true or not true at all if you are

certain that there can't be.

Maybe if we did not have the dark, cynical, desperate, fragile,

poverty-stricken worldview of the liberals, if we just said "no, things

can be good, we can be good people", then, if we truly understood

that and implemented the changes in behavior and institutions that are

downstream of that, we could have good governments.

So it may be that it is as though the Christian humanists (Black?)

could be saying "government is good -- or it can be good -- that is,

kings are good -- good kings are good, at least -- that is, Jesus, the

king, is good". So that would be the rejoinder to a libertarian, who

thinks that kingship / government are inherently dangerous and evil.

However, as (perhaps) Black points to, another dimension of

pursuing libertarianism is out of a love of not having anyone else tell

you what to do. Is there any validity to this impulse and are there

any dangers to it?

[This will connect to the validity of self-determination:] Maybe

there's a validity to the faculty that people have of caring about

things. It's not absolute, but we could say that it is prima

facie valid. If you care about something, you should care about

it, unless there's a good reason not to.

I read a book a number of years ago which has stuck with me, by

Sheena Iyengar, called The Art of Choosing. I'm not good at

remembering exactly what books say versus what I think of occasioned

by them, but either way, I was left with the thought "what I really

care about are the things that I want to be able to choose myself"

["what I want to choose myself are or relate to the things that I

really care about" is a clearer way to express what I meant].

There's a correlation between caring, finding valuable, and wanting

to make sure things turn out according to your caring.

In much of my life I don't have strong preferences, but at the time

I read the book I realized that the freedom to think about whatever subjects

I needed to think about was really important to me, to the extent that I

couldn't get married and have a family, because I couldn't risk being

committed to a high-paying job (to support them) that would monopolize

my thinking. Iyengar was raised as a Sikh and raises the prospect of

arranged marriage in the book. I discovered, while thinking about the

book (working through an exercise in it) that I didn't mind the thought

of arranged marriage in itself. (If somehow it didn't threaten my

"freedom" of thought!) [It looks like I make demands on reality: freedom

of thought.]

I put "freedom" in quotes because I am not really free. My thinking

is as constrained as anything. I don't choose the things that

speak to me. They speak to me. It's because my thinking is

constrained by something that is not legible to society that I need

freedom from society. I understand that it's fair for society to

ask me to not make trouble, in exchange, so generally I do abide by

basically liberal ideas of "my rights end at the point that I want

to constrain other people's liberty". So given all that, I am happy

that I live in a relatively liberal setting (the people around me

generally give me space, and I am free to be an individual

and not get caught up in a group's undertow.)

I don't think that is quite the same as the potential strawpeople

who say "I don't want the government to take my guns and make me use

a vaccine". But I can relate to people like that. I want to be left

alone to be myself. It's an understandable human desire, and it's prima

facie valid. If you've never had the misfortune to have someone

close to you try to tear down who you are, it's like having someone

reach into your brain and put their fingers in it, breaking the

interlocking parts of it, re-engineering you when you express who

you really are. Even if someone is wrong, tearing down that wrongness

at all costs tears them down as a person, just like even if someone

is living in the wrong house, setting it on fire to smoke them out

could kill them. We should have defenses against other people trying

to change us.

(In a previous post, I brought

up the idea of "ego-respect" vs. "survival-respect". "I deserve respect"

in the "ego-respect" sense can be the sort of thing gang members say

to justify killing people over (some meaning of) honor. But in the

"survival-respect" sense, it can be what abused people can say to justify

getting away from their abuser. It can be a little bit unclear sometimes

if a given case of respect being called for is ego-respect or

survival-respect, and being too good at clamping down on ego-respect can

threaten survival-respect (maybe being too supportive of survival-respect

can feed ego-respect?). Similarly, there could be an analogous

phenomenon of ego-freedom vs. survival-freedom.)

God creates us (and makes us) to be who we are -- so to an extent,

that is not something that is anyone else's business.

However, it is true that people are not born loving God with all

of their beings. Obviously we do have to change. And perhaps the

libertarians or anti-vaxxers, in distrusting change as it comes from

leftists or liberals, are really distrusting change of themselves in

general and therefore are at risk of shutting out God's voice.

A lot of what I've said above seems a bit orthogonal to what really

matters (for instance, it's not clear to me that my preference for

thinking my own thoughts -- if it is not a constraint that I don't choose

-- is necessarily better than being caught up in a group's thinking, nor,

at the same time, that being a member of a group is better than

being an individual). But this issue of potentially not trusting change

itself [change in itself] seems to directly connect. People really could

be setting themselves up for not connecting to God, through politics.

Whatever they prefer over total commitment to God is an idol, and whatever

prevents them from connecting to God, whether they understand that

that [that preventing] is what is going on or not, may further idolatry or

prevent full love of God. (The thing to watch for is, when we go to tear

down other people's idols and set their temples on fire, that we aren't

trying to shoo them into our temples to worship our idols.)

A lot of what we talk about is orthogonal to whether we love and

trust God, or only somewhat "at-angles" to

it.

I have trouble staying on topic sometimes, so I will try to take

a moment to keep score. Let's say that the topic of "does 'kingship'

seem like a bad thing to you?" is the point of this post so far.

I said that I can see value in firm, consistent government in terms

of its ability to suppress violent gangs, who seem to be the default

rulers when there is no government. (Maybe this only seems to be true

and isn't always true?) This is in line with what libertarians

want, since all (except the most radical) accept some kind of state --

perhaps a firm, consistent one.

I claimed that liberals and libertarians tend to have a dark view on

life (particularly on power and the concentration of power), while the

post-liberals / Christian humanists tend to have a not-as-dark view on

life, power, concentration of power. By having higher expectations,

post-liberals / Christian humanists could actually bring about a better

government, proving their expectations valid and showing that kingship

(even as a case of the concentration of power) can be a good thing.

Then in the next section I considered whether libertarianism (or

liberal values in general) might be valid, and how they might be

dangerous. I said they might be valid as expressions for protecting

the integrity of individuals (the prima facie validity of

caring about what you care about and being yourself). Also, God

has rights over people which trump the social order. However, a

danger of liberal / libertarian values (or of protecting who you

are from the interference of others) is to be unwilling or unable

to change at all (to not value change in general) and thus to be

unable to listen to the voice of God.

I realized at that point that much (or all?) of the discussion

preceding the recognition of that danger didn't necessarily matter.

People prefer this, or that. But the really fundamental issue

is whether people connect to God.

That is a good point to remember, and I should return to it

later. But for now, I'll resume my discussion of the value of

kingship (in light of alternatives to it like libertarianism).

Maybe kingship and individual liberty (or even libertarianism?)

are not in conflict, or are not as much as one might initially suppose?

I have defended some of what liberalism ostensibly defends [individual

freedom], and that's how I can appreciate liberalism. But a king doesn't

have to constrain people in any kind of absolute or granular way -- and

historically, even earthly ones hardly could have, given their

resources. Maybe they could have within their own courts? But that

is them acting on an interpersonal level. (Ironically, for me, I may

not care so much about the government, as I do about the social order

[like the king acting as just another member of the royal social circle,

the scene of humans relating human to human, rather than as wielder of

vast state power], and yet my experiences with the social order might

inform my (mild) appreciation for the possibility of libertarianism.

(Or my lack of outrage against it.))

That's a practical reason [limited resources] why kings do not

constrain liberty even if they want to. What if kings just decided that

they weren't going to constrain their subjects' liberty? Is it that

simple? I'm reminded of a vivid image from the effective altruists.

One AI safety researcher (Buck Shlegeris):

[Context: illustrations of the principle "problems solve

themselves".]

Another one is: "Most people have cars. It would be a

tremendous disaster if everyone bought cars which had guns in the

steering wheels such that if you turn on the accelerator, they

shoot you in the face. That could kill billions of people." And I'm

like, yep. But people are not going to buy those cars because they

don't want to get shot in the face.

(source)

Aren't humans reasonable? Don't we want a nice world? Don't

we not want to shoot ourselves in the face? Or even make things that

could shoot other people in the face? Won't we want to design systems

of government that work, or raise up people to be in positions of

government who don't do a bad job? So why can't kings just not

abuse their positions of power? Obviously they do sometimes. But they don't

always, not maximally. And arguably kings (or whoever is in government),

start their lives wishing to do the most good, but when in office

have to deal with "realities" (like violent gangs which are hard to

imagine controlling without violence, or the Molochian

dynamics of having to maintain a strong (capitalist) economy, in order

to support a strong military, to keep other countries from invading).

If we zoom out and squint, humanity as a whole is good, full of well-intentioned

people. And this is even true of people in government -- as long as

they don't forget who they really are.

Those are some ideas about how earthly governments (even kings) could

just not in practice use their authority to be abusive. [Reasons why] if

we are consequentialists [if we are considering consequences], we don't have to

worry about the spiritual reality of authority leading to abusive outcomes.

I am unsure whether post-liberals want to restore monarchy on earth (I don't

know enough to say either way), but it is not their most obvious emphasis.

I would guess that they are more into being culturally non-liberal more so

than legally or politically non-liberal (granted that "political" might be

hard to separate from "cultural" sometimes). [So I don't know how likely a

literal inauguration of monarchy is, given their ambitions. Still, I can

allow that in practice, kings do not have to be abusive.] However, the

important topic to consider is "is kingship [as a value] bad, and how does

it fare against alternative values?" and the specific occasion for all of

this is "What about Judges? What about Jesus' kingship? What about kingship

seen through a spiritual lens?" [What aspects of kingship are good or

bad, not just from a secular or humanist perspective (the "abusive" above)

but from a radically theistic perspective?]

I don't think it's impossible to imagine a world which is, from a

human's eye view of how the world works, libertarian, but in which in

fact Jesus is king. The thing that allows for authority in the absence

of external coercion or direction is an internalized law (and whatever is

epiconceptual / episcriptural / "epilegal" to

that law). That's more or less what I had in mind when I first replied to

Black ("maybe libertarianism is the best and we are not worthy of it").

The king writes the law and we keep it -- no need for police forces or any

kind of coercion. I think libertarianism (in an idealistic form) may long

for a world where people are free to do what they want. And I think that's

a good thing, just so long as they are keeping the law.

So I could reveal myself now to be defending a position of "laws are better

than direct involvement -- the king is more legislator and facilitator

of adoption of legislation than he is direct leader". I am unsure that

I want to defend that position so baldly, that I should define myself

as taking that side. But for now I'll say it's my view -- certainly

I lean toward it.

This emphasis of mine on law and hands-off kingship has a lot to do with

my upbringing. I was raised in a Church of Christ (a somewhat unusually

free-thinking and moderate one). The Churches of Christ are very American

in some ways (for instance, they have no denominational structure), but

also very un-American (they like obedience and law). They are

hyper-Protestant (Sola Scriptura to the point of rejecting theology) and

also anti-Protestant (they are fairly okay with saying "salvation is by

faith and works" and believe that undergoing a physical act (baptism) is

a necessary part of salvation). One of the classic Church of Christ

doctrines is that the Holy Spirit's actions on Christians are solely

through them reading the Bible that he wrote, like if you had a

pen pal whose sole actions on your mind were

through writing letters or emails.

Most of the really "pungent" Church of Christ doctrines were not taught

or emphasized in the church I grew up in, but when I discover them later, I

think "yes, I like this emphasis". Perhaps I am genetically Church of

Christ (plausible since both my parents and three of my grandparents

are/were members). However, I am not sure I would want to be dogmatically

in favor of all the points given in the previous paragraph. Notably, I

don't think the Holy Spirit's actions are only carried out through us

reading the book he left behind. However, I think that's a good dimension

to consider, that the Word of God -- not just in some mystical, spiritually

empowered, supernaturally gracious sense, but just the (relatively) plain

sentences that we can understand like we can understand a pen pal's email,

is the action of God on us, is God's presence and power. This view leans

toward "God is your friend" rather than "God is great and powerful" (which

I think follows from the polar opposite view of the Holy Spirit, which

would be like a hyper-Pentecostalism (that is, the view that the Spirit

is only tongues of fire, rushing winds, prophecies, and whatever else

the Pentecostals restored and which the cessationists deny. I would

guess that there aren't any real hyper-Pentecostals, that Pentecostals

all acknowledge the quieter voice of the Spirit.)).

"God as friend" connects (in my mind) to the idea that God is kin, and

that we know him by kinship. So internalizing his values is more valuable

than being ruled over by him. I doubt Black would object to that idea,

so maybe if there remains a difference between me and her, it could be in

something like "how should government look on earth?" or "how should we

relate to the idea of kingship?" or "how should we relate to the idea of

law?"

At the time of writing this, I don't know that I have a strong preference

for any given government on earth. (Maybe against abusive ones, but not

for any particular non-abusive one -- some idea of what I mean about abuse

being given earlier in this post. [For instance, abuse as violating the

integrity of an individual.]) I suppose the ideal earthly government

would be one in which all the adults were holy people with God's interests

first in their minds and actions, and the only challenge remaining being

the education of young people to become such adults, and maintaining

physical sustainability. A non-coercive government would exist to

coordinate large-scale resources. It wouldn't have to be coercive because

everyone would of one mind. The only coercive government would be that of

children being ruled by their parents or teachers, and only to the extent

necessary. That sounds fairly libertarian to me, although maybe it sounds

like some other label if you take it vaguely enough. However, the ideal

earthly government may never be possible, and in the meantime I don't have

a strong preference -- for instance, the US government is pretty good in

many ways, but it may not be the best.

My vague vision of ideal earthly government does not sound like one

that falls out of the bounds of Christian humanism (as I understand it),

and I guess that it is not a sticking point between me and Black. Again,

I don't have a strong preference and would be willing to live under

different governments, likely whatever else could fall within the

bounds of Christian humanism.

This leaves the questions of "how should we relate to the ideas of

kingship? and law?" I don't really know Black, but I'll give some

different perspectives on kingship and law that occur to me, some of

which may (or may not) happen to apply to her. These are probably

strawmen to some extent. (These are guesses and are likely not the

full picture.)

One reason why kingship could be emphasized is to keep humans down.

Humans need to know that they must think small and keep perspective that

they are not God, they are not king. Because there is a God, they are not

God and because there is a king, they are not king. Keeping humans down

is a good thing (maybe) because humility is the chief virtue. Humble

people are the most beautiful people and we can trust them interpersonally.

The real danger in the spiritual life is pride.

Keeping humans down is a very attractive view -- humans seem to like it

a lot. I don't think it's really Jesus' main emphasis. I would warn

Christians away from it to the extent that it keeps people from using their

talents to the full, and places humility even above the love of God among

the virtues. If we are maximally humble (at least for an obvious meaning

of "humble"), how can we claim to know the truth? So humility could

alienate people from God.

But a more steelman version could be "Jesus as king tells us not to keep

ourselves down, and because he's king, we obey." I guess you could say

that laws also keep humans down / humble them. [Kings and laws can both

support and undermine "keep humans down".] So that's not the real

sticking point between me and Black. But maybe if laws are emphasized,

it could become the case that humans don't need the king-relationship as

much, that while God is king, that's not really something that God

regards. It's like if your dad was really good at something, and you knew

you'll never be that good at it no matter how long you lived, and he knew

it too, and he would never put you in the position to do his job, but he

didn't really care about his own competence and it barely came up because

he could talk to you so freely, given all the things you have in common

because you grew up to be like him [law teaches kinship (sonship /

daughtership)]. In your relationship with God, his kingship is less

relevant to both him and you than your mutual kinship. (Perhaps a good

illustration of the phenomenon of unlike people being kin

comes from Ursula K. LeGuin.)

Another reason why kingship could be emphasized is because humans need

a power-figure in their lives, and God (as king) represents one.

Pentecostalism is very popular in the developing world, and from the

little I have seen of it online, it seems like there can be a

desperation for the power of God, because people in the developing world

are often desperate. I wouldn't want to get in the way of what allows a

desperate person to function. So there's a prima facie value to

the psychological support given to people who (in a sense) need a power-figure

-- maybe really need it at that time of their lives.

(Later: maybe "people in the developing world are often desperate" is

less true than "sometimes desperate"? Also, do I expect that this post will

never find its way to someone who (apparently or really) needs to consider

God to be a maximally powerful being in order to hold their life together?

If I think it could, how would I contextualize all of this to make it

somehow not too destabilizing? More details may perhaps be found below,

but I could say, briefly, that as long as you are true to God, no matter

how bad things are in this life, you will someday participate in his rest,

and God is always present in your life. No matter how bad things are, you

can always love God. There are other bad outcomes besides what may

happen to you -- other people may not remain true to God -- but they

are not under your control, are not your responsibility. They belong to

God. Your responsibility is to obey God. If someone else is lost, you

may mourn, but you will be okay, overall. Your mourning will not

overwhelm you, and you will affirm it out of love, rather than be

subject to it as a slave to automatic emotional reactivity.)

One of my tweets claimed that trust in God

was aided by a more hands-off approach. I think the lived lives of people

(in developing countries or in ours) is that, if both our

theism biases and atheism biases aren't

dominating how we see the way things plainly look, sometimes it looks like

God is hands-on, and sometimes hands-off -- sometimes his intervention in

the world in which we are forced to care ("lived life") is present, sometimes

absent (absent to the point that we doubt that he exists sometimes).

Which produces more trust in God, when God is hands-on, or hands-off?

Trust is complicated. It is inhibited by

betrayal (the fruit of a hands-off world). But it is also inhibited by

satiation and perfect safety. If things worked out okay, we wouldn't trust

as deeply. We wouldn't trust as deeply, we wouldn't be as alive

to trust. Trust is connection as well as acceptance. We have to care in

order to trust the most. So we have to engage with reality. All

that to say that some mixture of hands-on and hands-off is needed and that

"king" versus "judge" are at different points on the same scale. "Judge"

(or, God as king as in the days of Judges) says "more hands-off", while

"king" (or, Saul/David/Solomon(/Jesus?) as king) says "more hands-on".

(Or for "hands-on" we can also add "more firm and consistent" and for

"hands-off" "less firm and consistent / less established".)

Unlike developing-world Pentecostals (as I understand them), the

spiritual reality that has been my problem has not been poverty or

powerlessness. Rather, fakeness is what has driven me, which I think

connects to the ideas of satiation and perfect safety inhibiting caring

and therefore trust and life. I suspect that in some ways, I'm living

in the future, in the hyper-developed world. So to me, becoming real

has been a kind of life challenge, and to internalize a law (plus its

epiconcept or "epilaw") allows me

to become real. The danger for a developing-country Christian is to be

weighed down by poverty (and perhaps from that despair and turn away

from God) or to turn to sin out of desperation and then maybe come to

love it (a real danger for narcotraffickers), but for me it is to [be] turned

into a spiritually dead person by wealth. I don't think about fakeness

anymore (although I think I would if I tried abandoning my values), but

instead I am concerned that I won't be true to my values, that I will

sink into a state where life is nice and I don't deeply care about

God. A God who was too hands-on would prevent me from being hungry

for him, would allow me to become numb through ease and pleasure. So I

desire poverty in general, and this can connect to the poverty of

not having a king (or of having a Judges-era God as king rather than

one more like Saul, David, or Solomon), of having a worldview in which

the ideal government is not firm and consistent, so that instead I rely

on God.

Could a king decree "you are real!" and it would be so? The related

questions of "Could God decree 'you are sinless' and cause you to be seen

that way by him?" or "Could God zap you and make you in fact sinless?"

could be (or maybe have been) big controversies in Christianity. I

think most Christians think that God can zap you and make you sinless, or

at least that seems fitting with the Christian culture I've seen.

Otherwise how could anyone go to heaven? And I agree with the existing

Holiness movement (as I understand it) that we receive holiness from God,

that it is God who makes us not have our sinful habits. But, that's

only part of the story, because we have to repent of our own sins

ourselves. We have to acquire the values of God, and that's

something he can't do for us, or else it would be he who valued

them. Our sinful habits may keep us out of heaven and be something God

can deal with unilaterally, but our misaligned values are something only

we can do anything about, so that it is we who [come to] love God.

So a king who wanted kinship (someone as real as him) would do better with

laws than with direct intervention.

Though I said earlier that the ideal earthly government is one which

is sustainable and focused on education, that situation sounds fairly

stable, calm, and thus psychologically wealthy, a temptation to no longer

deeply care. So I think for such a government to seem trustworthy to me,

though in itself it may be stable, calm, and functional, the culture around it

would have to emphasize the insufficiency of

wealth, to mourn the loss of poverty, to feel the lack of lack. Even feel

the lack of chaos, terror, and horror, saying "When we were afraid, we

turned to you with all of our beings, but we are no longer afraid. How

unfortunate we have become." (Or which may be the case for many of us

"When we were afraid, we had the opportunity to turn to you with all

of our beings, but we did not take it, and now we are no longer afraid.

How unfortunate we have become.") Poverty is hunger, and hunger cares.

I think a natural rebuttal to poverty being needed to value God is

to bring up gratitude. When we are wealthy, we redeem it with gratitude,

by being thankful to God for how good our lives are. Maybe with gratitude

we can turn to God with all of our beings. I don't think it's as natural

to as deeply turn to God out of a sense of gratitude than out of fear (what

I think of when I think of "deeply" touches on a different part of a person

than gratitude does). I think of the closeness that a child might feel

with his or her parent after being comforted after a serious upset. But

maybe for other people it's different, or could be different in an ideal

society where we are trained to interpret things properly. However, even

in heaven there's something missing, something lost, if we want to get a

lot out of the verse that says "Greater love has no one than this, that

someone lay down his life for his friends." (John 15:13). In heaven we

can no longer have the greatest love, a casualty of everyone remaining

having been completely saved. So, along with the lost who will never be

alive again, God could mourn the loss of part of himself, part of love

itself.

(Also, true gratitude may necessarily be a form of poverty as deep as

that of turning to God in fear, and many (or all?) of us may need the lived

experience of poverty in order to develop it.)

So if kingship is an attempt to have an established government that

prevents psychological poverty, or if a love of kingship is an attempt

to make that true in the space of one's own valuing life, then it might

be better to value less-established governments, "judge-like" (like the

way things are when God is king, rather than the way things are when

humans are king).

In the above, I tried to say that God would prefer to relate to us

as friend and father, and that by means of law (hands-off kingship /

king as legislator rather than direct leader) we learn how to become

like God, fully mature and thus capable of deeper relationship with

him. From that, I would say that I have an ambivalent relationship

with the idea of "kingship". I don't deny that there is such a thing

as kingship, or authority, and while I have a personal taste for law,

I don't think that either that or kingship are really very interesting

in the end, though they may persist eternally. Such spiritual

realities are means to the end of a familial and friendly relationship

with God, a simple intimacy.

What I could try to do, and, as noted below, may try to do in the

future, is read through Judges and the books that talk about the kings

of Israel, and perhaps other parts of the Bible, to see if there are

any clues as to why God would prefer the somewhat anarchic Judges days

over, say, the settled and established days of Solomon. My guess

for now is that the reasons given above, or some of them, may have

something to do with why God preferred to be that kind of king (a

more hands-off one) than to use more established governments like those

of Saul, David, and Solomon. God may share with libertarians some of

their values, and prefer a kingship that offers liberty and insecurity,

which can be the foundations for love and trust of God. When we

choose too little freedom and too much security (or if we have an atheistic

liberty and insecurity as the foundation of government), we

reject God as king over us.

There is a difference between libertarian and Judges-like government.

Liberty at the expense of security might plausibly be libertarian

values for some meaning of "security", (i.e. favoring the insecurity of not

knowing if you have a job [will be able to find a job] rather than of

wondering whether your contract will be enforced), but most libertarians

(I would guess) value wealth, and think that wealth (in the form of liberty,

or economic wealth) should follow from ideal government, whereas I think

God (as love) would be ambivalent about wealth, and wealth would not be the

main point of his government.

Isn't wealth basically that which God created in the beginning and called

good, and even very good? Arguably so, but there's a mixedness to that

goodness. In the very fact that it is so good, it becomes a temptation

to be valued more than God. Perhaps God creates wealth so that we have

something difficult to renounce (or become genuinely and fully willing

to renounce) in favor of him, so that our love is even more tested to

the point of reality, than if it was only tempted by being confronted

by suffering or poverty.

Now, to circle back to the beginning where I mentioned the situation

in the Northern Triangle... does God prefer that over the state of affairs

in the United States, if he preferred Judges-era Israel over Solomon-era

Israel? One could argue that God is not as much king in the Northern

Triangle as he was in the time of Judges, and that would give an easy

way to decide. If the United States is not under God's kingship (except

in the sense that all reality is) and neither is the Northern Triangle,

then we might as well minimize horror, since horrors are evil, and in

that way do what God wants. But I could say in reply that rates of

Christianity are high in the Northern Triangle (greater than 80% in all

three countries as of the 2010s). Maybe the people there

are gaining spiritually, despite living under the terror and futility-making

of the gangs.

It's interesting that Jesus says, in Luke 6:

24 "But woe to you who are rich! For you have received your

consolation. 25 Woe to you, you who are full now, for you will be hungry.

Woe to you who laugh now, for you will mourn and weep. 26 Woe, when men

speak well of you, for their fathers did the same thing to the false

prophets.

Maybe poverty is a blessing that God will share with all of us fairly.

This perspective does make it hard to evaluate altruism. Is it right

to alleviate the poverty of chaos and evil in the Northern Triangle

(if we could figure out how)? It doesn't sound like the worst thing

you could do. But is it a really necessary thing? The people there

(other than those who perpetrate the evil according to their own wills)

are storing up all the blessings of the beatitudes, which are the

counterpart to the "woes" in Luke 6. What is it that is really

up-for-grabs, a site for gain or loss, such that if we increase things

on some axis, things actually get better for people in God's eyes,

and if we decrease along that axis, things actually get worse?

I would think that holiness, closeness to God, and the like are

that axis that should be maximized, and that the case for suppressing

gangs in the Northern Triangle would be to keep the gang

members away from the intense temptations of gangs, and allow them

to find the anti-temptations of their

culture's Christians (when those Christians are at their best), or

whatever other source of anti-temptation they might encounter, which

the gravity of gang life draws them away from. It could well be

possible to suppress gangs without people turning to God, but in

principle, it might help.

What could be done for the United States? One way to look at the

United States is that we are stuck with an established social order,

a firm and consistent government, because it simply is unnatural for

people to choose otherwise. In a way, we should hope that is not

true, lest we fall into some kind of situation where we feel morally

/ socially compelled to trade away all

freedom and trust in God for safety and pleasantness, because

our preference for the United States' establishedness over the

Northern Triangle's lack of establishedness comes from our ingrained

social value of safety and pleasantness. It may not be the case

that we value the United States' government for that reason, and

thinking optimistically, maybe we can say "no" to the psychological

fuels of consumerism (hedonism and preference satisfaction) even if

it currently is our reason for such valuing. So maybe (theoretically)

we have a choice (one which we may even have practically in the

future) as to which world to live in -- we could choose a

less-established world, one more like the Northern Triangle and less

like the United States.

Should we take that opportunity? I find it difficult to say yes --

perhaps I am too much a product of my biology and culture. If I can't

say yes, I can offer something like what was mentioned above, where

we realize in a deep way the insufficiency of our developed earthly lives.

We might spend the time that we currently do on entertainment to contemplate

how lacking our safe, comfortable world is, how it is not ideally tuned

toward producing holiness and love of God, the only fruits of this life

that matter in the end. Try as we might to replace stress and risk

with anti-temptations, there is a dimension of love that we will seldom

if ever experience if we never pursue and undergo the cross. We will

have made discipleship of Jesus obsolete (to some extent this is already

the case).

It might be possible to say yes [to the choice of a less-established

government] if we were all (or generally all) Christians (given that young

people are in some sense not born Christian) and we thought of our

civilization pursuing the cross by disestablishing, in order to rely on

God more. We might think of it as civilizational trust. We wouldn't rely

on the machinery of government to enforce laws, but on how we instill those

laws in each other, most essentially on the extent to which they are

written in us through our own consent. This would be a case of the cross

(risking death for the sake of others) if a Judges-like government led to

greater trust in God and thus lower rates of people failing to really love

God.

I have reached the end of what I had to say, more or less off the top

of my head, and now I am curious to see what the Bible actually says.

So, as I thought I might in previous paragraphs, I will read Judges and

the following books up to the end of Solomon's reign to get some clues as

to why God preferred the judges-era pattern of government over the

kings-era one. (I could expand my reading to include the period of time

the Israelites were in the wilderness, since it's analogous to Judges, and

to read about the kings after Solomon, but that would be a lot of reading,

and I'm already delaying the release of this post by a bit by doing as much

as I plan to. (Similarly I could try to compare and contrast the

less-established eras of church history (first three centuries, persecuted

churches, poor churches, churches in chaotic situations) with the

more-established (post-Constantine, national, protected, wealthy churches),

but that would be even more reading.) I hope I'm getting a reasonable

sample of the difference between less- and more-established governments

with the readings I intend to do, at least for now.)

Having read the Bible, and reflected, here are my thoughts on God

and establishedness.

Three caveats: 1) When I read, I just read the ESV without doing any

deeper study. There is some chance that I'm not getting what a scholar

would. Whether this is actually a problem, I'm not sure. I would

guess that the ESV is usually not misleading (that's the point of

a translation). But I would guess that there are at least a few

things I'm missing or getting wrong. 2) I only read Judges, 1 Samuel,

2 Samuel, and the part of 1 Kings about Solomon. But Exodus through

Joshua has similarities with Judges, and the kings after Solomon

are often like Solomon in that they are established. Also 1 and 2

Chronicles overlap with the readings about Saul, David, and Solomon.

I considered reading all these, but thought that it was better to

not put too much time into this post, at the risk of missing some

nuance. (And as I went I realized that the entire Bible is relevant

to questions of establishedness and disestablishedness.) I hope that

the additional readings would not (or will not) overturn too much of

what I have seen, but only add details to the same overall picture.

3) I am biased in favor of my own preferences and intuitions. I don't

feel like I am (I tried to be fair-minded in the verses I highlighted

and conclusions I drew), but I know that I am.

(Therefore this post is not a maximally-established thing in itself,

and calls for some kind of improvement or criticism.)

My method in reading the selected passages was to look for and

elaborate on references to the concepts of establishedness,

disestablishedness, establishment, establishing, and disestablishing,

both psychological and political, as well as to references to God's

intervention. A rough definition of establishedness is "the state of

having been made so, put together, organized, given a place" (and also

some connection to whatever else the common meaning of "established" is).

A rough definition of "establishment" is "a thing that continually

establishes something". I assume that psychological establishedness

is the bedrock reality, and political establishedness emerges from that

(and then turns around and affects individual psychological

establishedness). (If all the soldiers are afraid, the army is less

established -- it is weaker, less organized, less a body of people.)

I found that there were situations in my reading that were "mixed".

("Mixed" things, in themselves, call for feelings of ambivalence,

just as ambiguous things call for a sense of uncertainty or undefined

thought.)

I was interested in the following questions: what is the difference

between the Judges-era of God's kingship and the human kings-era of

God's kingship from a spiritual perspective? Why might God have

preferred the Judges-era? Did God intervene more, or less, in one

era or another? I thought that the main spiritual difference between

the Judges era and the Kings era was establishedness.

The really important field (with respect to

establishedness) is establishedness on an individual level, but

political establishedness affects this. With a king, a political

body is more established than under a succession of judges. So

that is why I focused on the theme of establishedness.

I think the idea of establishedness might be a good,

general one. I found myself taking it different places in the text. I

am not sure it is the best concept, and will only endorse it (for now)

within the context of this post. (My uncertainty about it being

something like: Why does this exact concept need to exist? Is there a

better mapping of relevant phenomena to a name?)

One piece of my intellectual background that's worth mentioning here

is the story of my acquaintance with and adoption of the New Wine System.

When I was in college, and just out of it, I spent a number of years

(maybe five?) puzzling (at times) over soteriological verses from the New

Testament. "Salvation is by grace through faith apart from works, so

that no man can boast" says Ephesians. "People are justified by works

and not by faith alone" says James. "The work of God is to believe the

one he sent" says John. "God wants everyone to be saved" says 1 Timothy.

I thought of the different theological positions I understood (somewhat)

at the time: Church of Christ, Catholic, Reformed, Arminian Baptist.

The Reformed did pretty good with Ephesians (God is the one who saves, 100%),

but really bad with 1 Timothy in combination with Ephesians (unless they

were universalists, but I didn't think universalism was biblical). The

Arminian Baptists had figured out a way to reconcile Ephesians and 1

Timothy (those who choose to have faith are saved, apart from works), except

that them saying that people needed to have faith meant that those people

were doing the "work" of faith (John), and obviously they could boast about

it. (They could just choose not to, but they could also just choose not to

boast about other works, so if the "not boasting" thing is the point of

the Ephesians verse, it must be really hard to just not boast.) The

Catholics and Churches of Christ did pretty good with James, but not so

good with Ephesians.

I thought that everyone had difficulties interpreting scripture, and

I came up with my own weird way to reconcile things (when we obey, we

do God's will, so we are nothing but God acting in the world, but when

we disobey, then it is we who act -- a view I found out later was similar to

Lutheran monergism).

At some point, I faced the possibility of people (a particular person)

who seemed basically good going to hell, just because they (he) weren't

(wasn't) a Christian. My mind remembered the universalist-leaning verse

"every knee shall bow, every tongue confess that Jesus is Lord", and I

looked it up, and saw that it came originally from Isaiah. I searched

on a popular Internet search engine, for the verse in Isaiah, and discovered

the site for the New Wine System. It

looked similar to how it does now (I found it in fall of 2012), offering

resolution of scriptural difficulties. It talked about a different

kind of soteriology, referencing the verse in Isaiah. I was interested,

and thought that it might have (what I would now call) high expected

value. So I ordered the comprehensive exposition of it (New Wine for

the End Times) and read it.

I was first impressed by how it handled the issues that I had coming

in to reading it. My opinion at the time was that it dealt with the

verses mentioned above, and others, in a more natural way than the

stretchings that I suspected or had heard people making to get around

the apparently plain meaning of each verse. It gave a place for otherwise

obscure passages in its own context. Also, it offered a scriptural reason

to think that God wouldn't (in keeping with his 1 Timothy desire that all

people be saved) create people who through no fault of their own were never

adequately preached the gospel, and who therefore would have to go to hell.

But ultimately it was the part that I had least desire for going in

that had the greatest effect on me. The New Wine System is about the

Millennium. The Millennium exists to bring people to holiness, full

spiritual maturity (so that they no longer have any sinful habits, and

(I would now emphasize), they fully put God first in their hearts -- and

possibly full spiritual maturity encompasses other dimensions as well). It

inherently provides a scriptural explanation of where, for instance,

people who died in pre-contact traditional cultures could hear about

Jesus. If the Millennium solves that problem, it does so by "preaching"

holiness -- the Millennium exists both to include people and to bring

them to completed spiritual maturity. In most Christian cultures,

holiness is not necessary for salvation, but in the New Wine System it is.

This can be a powerful idea for anyone (I have some ideas for why

it might ought to be, here), but

it was particularly powerful for me. I had already had some interest

in the idea of designing better ideologies for altruistic purposes,

and this seemed to me to be an excellent way to motivate people to

be more altruistic. The idea was so powerful and obviously useful,

and also so Biblical (from what I could see at the time), that I

ran with it for years. I developed a natural theological support

for it (which, is somewhat helpfully sketched out

on this blog), to the point that now I think

imagining a God who is not in many ways compatible with the New

Wine System doesn't make as much sense, from a philosophical standpoint,

than imagining one who is.

Now it's been about 9 years since I initially read about the New

Wine System, and I have some uncertainty whether it is actually biblical.

I think the developer of the New Wine System may really have shown it

to be so, but I am a more critical reader now, and I'm more aware of

the possibility of Bible scholarship overturning an apparently "plain

reading" of Scripture. I think the developer did engage with more than

just the most plain (or naive) layer of Scripture study, but I wonder

if Bible scholarship could still overwhelm his theory. I am considering

re-reading New Wine for the End Times, but am not sure I understand

enough about Bible scholarship to make an effective reading of it for

the purpose of being critical.

(However, scholarship may be overrated. We haven't had

cutting-edge Bible scholarship, which has the latest, most authoritative

take on the original context and how the Bible fits into it, until

(by definition of "cutting-edge"), this exact historical moment. So

was all thinking about God fatally flawed and useless over the centuries

between the original reception of the Bible and right now? If scholarship

can overturn soteriologically-relevant doctrines, that seems to be a big

problem for the past (or for us now, given that scholarship could, at least

in theory, overturn them again). We could be misleading ourselves or other

people about how to properly relate to God. God obviously was on some level

okay with people seeking him without having the best conceivable scholarship,

and, in fact, this doesn't seem to be much of a biting of the bullet on a

New Wine view of soteriology. If it is true, it's okay, or more okay, if

we don't know how salvation works.)

(Also, I am not sure that we should view the Bible as something

revealed to the first century (or to Ancient Judaism), in no way

progressive. A priori, I don't see why I should be sure it

should be seen as an ancient truth to be handed down, high fidelity,

to the present, or whether it's supposed to be reinterpreted by people

in the present or future. I might be somewhat of a progressive Christian,

by entertaining this thought. I think the difference between me

and the usual progressive Christianity that I see is that I bend

the Bible (to the extent that I might, if the New Wine System turns

out to not be the most conservative reading after all) toward

a rationalist "theism" ("theism" as an ethical orientation toward

God's well-being and interests, by contrast with "humanism" as an

ethical orientation toward human well-being and interests), through

my natural theology, while they bend the Bible (to the extent they

do) toward a more secular humanism.)

So, given that as my background, I have I think an unusual take

on what matters. Maximizing holiness (a concept which could be a container

for all sorts of ways of being set apart to God: growing into spiritual

maturity, overcoming sins, loving and trusting God, setting aside idols

of whatever form, being fully disposed to obey God, pursuing and/or

undergoing the cross, and I would guess other congruent concepts and

phenomena) is ultimately necessary for salvation, and we should live like

it. The New Wine eschatology (the Millennium) allows this to be entirely

realistic. What is really dangerous is that which gets in the way of

completing the journey. Being satisfied, permanently, at 99%

of the way, is death. Or, whatever gets you to permanently stop growing,

at any level of maturity. Likewise, if anything causes you to be an

enemy of God, that is dangerous, and to become a permanent enemy of God

is death. (In the end, it's enmity that kills. Those who refuse to

grow all the way will eventually be forced to confront that fact, and

either choose to listen to God after all, or choose to be permanent

enemies). One would hope that the 1000 years of the Millennium could

undo damage done during the ~40-80 years on earth, but likely enough not,

in some cases, and that risk is worth trying to address. People can

acquire enmities with God or cherishings of idols that are hard to undo.

(Salvation could be defined as "how it is we end up in heaven and not

in hell". The New Wine view (which I think is supported

by natural theology) is that hell is temporary, ending in annihilation.

Over the long run, certainly over eternity, God in his holiness can't

endure any unholiness at all, so any holding onto sin (putting anything

ahead of God in our hearts), must cease, and if we make it so that we

hold onto it and never let go, then God must destroy us at some point.)

I've been a reader of Slate Star

Codex (now reborn as Astral

Codex Ten) since fall of 2016. A speaker at a philosophy club presented

short-termist effective altruism to me in 2013, an influential event on me.

In 2020 and part of 2021, I read the Effective Altruism Forum a lot. I've

been thinking about rationalist/EA ideas since 2013, more so since 2016.

I spent time developing views that related the New Wine system and my natural

theology to their concerns: the future, ethics, civilization, and perhaps

others. I am concerned (as I've somewhat expressed

here) that if humans get what they want (satisfy

ethical humanism (or humanism + "zooism", as is not-too-uncommon in secular

spaces nowadays), they may damage the prospects of people to adequately put

God first. (In reality, putting God first is what ethical humanism calls

for, if it takes God into consideration -- ethical theism satisfies ethical

humanism). Human civilization seeks establishedness, almost by definition.

But establishedness, especially highly optimized establishedness (both

political and psychological) could be dangerous -- strangely enough, more

dangerous in the end than the deaths caused by the genocides of the 20th

century (which didn't by themselves keep their victims out of heaven).

And, in principle, as unnecessary as those deaths, and as apparently up to

human initiative to prevent.

This causes me to have "priors" (a viewpoint going in to my investigation)

which cause me to be concerned with the danger of bad establishedness, and

to be more favorable to the prospect of good disestablishedness.

Establishedness is attractive and a natural end state for human psychology,

and if people settle on an end state which is not sufficiently connected to

God, that's dangerous. Disestablishedness is often inherently unstable and

unattractive, not what we gravitate toward. But it is our (only?) hope

(either through human initiative, or through purely divine intervention)

to break us out of bad establishednesses.

A brief synopsis of the portion of the Bible covered:

In Judges, Israel goes through cycles. They turn away from God,

go into a kind of "mini-Captivity" (a political disestablishment),

ruled over by neighboring kings, cry out to God, he raises up a

temporary ruler for them (a judge), the land has rest for a while,

then the people turn away and the cycle repeats. This has its

upsides and its downsides. It's apparently the form of government

that God originally wanted. But it does allow for some terrible

things to happen (as noted at the end of the book).

In 1 Samuel, the people get tired of this way of doing things and

want a permanent ruler (a king) set up over them, just like all the

other nations. God is unhappy about this but goes along with what

they say. He gives them a first king who isn't really the best king.

(Who was kind of obviously not the kind of person to make a good king.)

Perhaps God expected this king to do a bad job and motivate the people

to turn back from the monarchy? In any case, the king proves himself

so bad that even God "regrets" (controversial statement, explored below)

having made him king. God gets a better king anointed, and then

takes the future of the kingdom away from the first king. But not the

kingdom itself, immediately. A long process whereby the king-to-be

becomes more established ensues, and the first king is threatened by

this and is ultimately disestablished.

In 2 Samuel, the second king rules, consolidates power (establishes

the kingdom), but then sins in a major way. God disestablishes him

as punishment. The second king struggles with an attempted coup and then

re-establishes himself, grows old, and dies.

In 1 Kings, the second king has to establish his chosen son as king

(before dying), and then that son, the third king, enjoys the fruits

of his (third king's) supervirtue of wisdom (a gift God was pleased to

give him), as well as the fact that the land is now at peace (unlike in

the second king's day). This third king gets really rich and drafts

forced labor to build a temple to God, which God didn't really ask for

but goes along with. This king also builds a multi-building palace,

using forced labor. He impresses a lot of people (his own people, a

foreign queen). He has 700 wives and 300 concubines, some of

whom are foreign, some probably political brides to ensure peace.

Some of them turn him away from being true to God, get him to worship

foreign gods. God is angry at him for doing that and disestablishes

him somewhat. He raises up someone to cause a civil war and take

10/12ths of the nation away from the third king's successor. (That

takes us to the end of chapter 11, which is as far as I chose to go.)

I can also add a prelude and postlude to the above synopsis

(things I remember from past readings of the rest of the Bible):

Prelude:

First, God existed. Then he created the heavens, earth, and

first people. (Established reality.) The people of Israel began

long ago as a family consisting of one man (Israel), his two wives

and two concubines, and his 12 sons and some number of daughters.

God chose them (established them). The family had to go to Egypt

because of a famine (disestablishment), where they made a good first

impression. But they never assimilated, and as the generations went

by and they became populous, the Egyptians felt threatened by them

and enslaved them (politically disestablished). They made them work

to build things. After many generations of this, an Israelite who

had an aristocratic (Egyptian) background, but who had been away

being a shepherd, was called to come back and free the people (disestablish

Egypt, establish Israel) and lead them out of Egypt. So he did, and

the people wandered in the desert (in a disestablished state) for

forty years, preparing (spiritually and militarily) (being established

by disestablishedness of wandering) to enter the land that Israel and

his family had left from to come to Egypt. They enter the land

and drive out, kill, and sort of enslave the residents (disestablish

them), and this is where Judges begins.

Postlude:

After the third king's reign (in 1 Kings), there was a civil war, resulting

in two kingdoms descended from Israel (a disestablishing phenomenon

for Israel). The line of the second king and his sons kept a smaller

part, while a new dynasty took the larger part. The line of the second

king and his sons was sometimes good from God's perspective, while the

new dynasty and its successors never was. The good kings turned to God

and turned the people to God (establishing of spiritual relationship),

while the bad kings turned to foreign gods (establishing of spiritual

relationship) and turned the people away from God (disestablishing of

spiritual relationship). Both kingdoms were eventually conquered by

neighboring empires (the "Captivity") (political disestablishing).

The people of Israel remained in various captivities for many centuries. In

our day, there has been a revived political state called Israel (political

establishment) in which some of the descendants of Israel live,

which occupies land once held (and still held) by non-Israelites

(disestablishing them). Many of the descendants of Israel are lost, maybe they

died out or were assimilated into non-Israelite populations. So in

a sense the captivity has never ended.

God sent his son (also God) to become a human, born to

a descendant of the second king. He had a rightful claim to

the earthly throne of Israel, but was not recognized by them

and wasn't even really going for that. Instead he was shamefully

executed by a foreign empire, at the desire of the

leaders of Israel. (He disestablished himself to become a human,

and disestablished himself to die shamefully.) This was to accomplish

at least one of a number of possible spiritual agendas. He rose from the

dead a few days later (re-established), spent some time with his

friends, and then disappeared, going back to...? Possibly, suffering

everything "the least" beings suffer (being disestablished), and sending

his Spirit (also God) to do work in the people who consider themselves

his followers (being established). These followers created a sort of

parallel-Israel and built a big civilization (establishedness), which

split, split again in multiple pieces, had civil wars (disestablishedness),

persecuted (establishedness) itself and others, was tamed or captivated by

a secular (foreign? native?) power (a deceptive disestablishedness),

colonized and evangelized the world (establishedness), and overall

pursued the God-king's agenda, with mixed success, to the present day.

On this blog I use the World English Bible by default, so that is what

I use for excerpts, but when I did the reading I read the English

Standard Version.

Judges 6:

7 When the children of Israel cried to Yahweh because of Midian,

8 Yahweh sent a prophet to the children of Israel; and he said to them,

"Yahweh, the God of Israel, says, 'I brought you up from Egypt, and

brought you out of the house of bondage. 9 I delivered you out of the

hand of the Egyptians and out of the hand of all who oppressed you, and

drove them out from before you, and gave you their land. 10 I said to

you, "I am Yahweh your God. You shall not fear the gods of the Amorites,

in whose land you dwell." But you have not listened to my voice.'"

11 Yahweh's angel came and sat under the oak which was in Ophrah,

that belonged to Joash the Abiezrite. His son Gideon was beating out

wheat in the wine press, to hide it from the Midianites. 12 Yahweh's

angel appeared to him, and said to him, "Yahweh is with you, you mighty

man of valor!"

13 Gideon said to him, "Oh, my lord, if Yahweh is with us, why then

has all this happened to us? Where are all his wondrous works which our

fathers told us of, saying, 'Didn't Yahweh bring us up from Egypt?' But

now Yahweh has cast us off, and delivered us into the hand of Midian."

14 Yahweh looked at him, and said, "Go in this your might, and save

Israel from the hand of Midian. Haven't I sent you?"

Apparently in the days of Judges, when God alone was king, God could

appear pretty hands-off. Effectively, appearing hands-off is to be

hands-off on some level (you allow people to think you aren't involved).

(So, perhaps, if you see through the eyes of faith or philosophy that God

is always active in your life, you enable him on some level to be more